U

uncle_punk13

Guest

In 1903 a young gentleman from San Francisco by the Name of George A. Wyman rode, pushed, pulled, carried, and crawled his 1902 "California" brand motor bicycle from San Francisco to New York City. He achieved this monumental undertaking before the first automobile crossing by Dr. Horatio Nelson Jackson (in his Winton Automobile) and made better time, finishing his adventure in New York City at the "New York Motorcycle Club" rooms, 1904 Broadway, a mere 50 days after departing San Francisco. Amazingly, over half of Mr. Wyman's journey was accomplished by pounding over the ties of the trans-continental railroad as there were no "real" roads in the sense that we, in the modern age, have come to think of for Mr. Wyman to travel upon.

Patented and manufactured by Roy C. Marks, the 'California' motor bicycle was produced from 1901 through 1904; in 1904 this company was sold to "Consolidated Manufacturing" of Toledo, Ohio and became the "Yale" motorcycle. 1904 and 1905 were the only years for the "Yale California" ('Yale' make- 'California' model).

1903, the year of Mr. Wyman's coast-to-coast journey, was a landmark year filled with "first" accomplishments. The first "Harley-Davison" motorcycle was produced, the first year of Henry Ford's famous automobile company; as previously mentioned this was the year of the first automobile crossing of the U.S., the year the first Tour De France bicycle race was run, and the first flight of the Wright Brothers airplan- just to name a few.

George A. Wyman's account was originally published in a series of articles, in his own words, in "The Motorcycle"; a periodical of the time dedicated to motorcycling. "The Motorcycle" was a relatively short-lived periodical, in publication from 1903 until 1906, and yet played a key role in the history of motorcycling. George A. Wyman's incredible account was in their premier issue (Issue 1, Volume1, June 1903).

Unfortunately, this accomplishment was for the most part lost and forgotten. George A. Wyman never received the credit he was due for this historic feat. This series of articles was found and reprinted in a special edition of "Road Rider" magazine (courtesy of the late Roger Hull) in it's complete form in the late 1970's (1979). Yet again it was lost and forgotten until published, in installments, in "The Antique Motorcycle" a publication of the Antique Motorcycle Club of America. Still Mr. Wyman and his accomplishment remained somewhat obscure. In 2002 a friend of mine discovered it and I received in the mail a manila envelope containing a Xerox copy of the Story.

At once I began to read this astonishing account of trial, failure, and triumph. Once finished, I immediately started over again; scarcely believing what I held in my hands! I became enthralled with George Wyman and his incredible feat. I was moved by the great grace and tickled by the humor with which he endured the hardship of this adventure. For years now I have been doing research to find out more about Mr. George A. Wyman, and in July 2003 arrived back home from having finished re-creating his incredible journey to celebrate the 100th anniversary of his achievement.

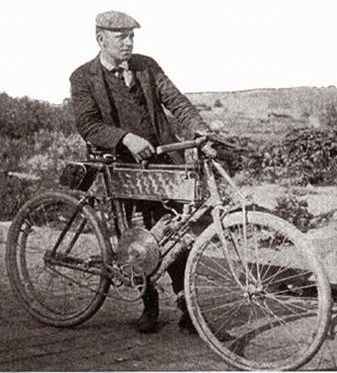

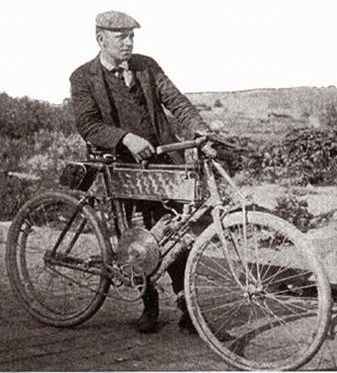

Born in 1877, in California, George A. Wyman at age 25, who was a member of the Bay City Wheelmen and a bicycle racer, became the first person to cross the Sierra Nevada Mountains with a motor vehicle in 1902; riding his 1 1/2 horsepower California brand motor bicycle to Reno, Nevada for a bicycle-racing event at the Reno Fairgrounds. George arrived on August 31st, 1902 awaiting the arrival of his comrades who brought his racing cycle along by rail one week later for the big race, against rival cyclists the Reno Wheelmen, on Sept. 7, 1902.

(photo of Wyman at a race in Valejo, CA 1902)

It was this trip to Reno that gave Mr. Wyman the inspiration to attempt the first crossing of the American continent on his motor bicycle.

To quote George (from his original 1903 text) while he was traveling over the Sierra mountains:

"I was traveling familiar ground. During the previous summer I had made the journey on a California motor bicycle to Reno, Nevada, and knew that crossing the Sierras, even when helped by a motor, was not exactly a path of roses. But it was that tour, nevertheless, that fired me with the desire to attempt this longer journey - to become the first motorcyclist to ride from ocean to ocean."

George A. Wyman left the corner of Market and Kearney streets in San Francisco, CA at 2:30 P.M on May 16, 1903 and arrived in New York City on July 6, 1903; enduring many hardships and heartbreaks while en route, yet he still manages to tell his story with a great grace, humility, and wit that could only be described as true American spirit.

George did in fact become the first motorcyclist to cross this great land of ours, he then disappeared into obscurity receiving no credit in the pages of our history books for his accomplishment. He also seemed to have just disappeared; we have been doing genealogical research (along with all of the other research concerning the vehicle, the geography of the time, the route traveled, etc.) and have only recently had a breakthrough with the rest of his story. Fortunately, we have been able to discover a little bit about what happened to George A. Wyman after his continental crossing. Here is what we have discovered:

It would appear that George continued to follow his interest in motor vehicles as he worked in different capacities relating to motor vehicles.

According to the 1910 census George had returned to San Francisco where he was working as a mechanic and chauffer, while residing at the Dorel Hotel, 1507 California Street. The 1920 census tells us that George, at age 43, was at this time married with three children, and was working as a second hand automobile dealer / salesman. His wife Nellie Wyman, (maiden name Lovern) age 41, had brought a child into the union; her son Harold, age 19, was a clerk for the Railroad. George and Nellie had also conceived two children of their own- son William (Billy), age 4; and son Richard, age 2. George A. Wyman had relocated from San Francisco by this time. He and his family apparently were now residing in Eureka, California. In the 1930 Census, George is still living in Eureka, CA with his two sons William and Richard. George is now working as an automobile mechanic. There is no record of his wife Nellie residing with him at this point.

Through a search of the Social Security Death Index we discovered that George A. Wyman, the first motorcyclist to cross the Continental United States, left this world November 15, 1959 at age 82 in San Joaquin county, CA. Furthermore, we found that his youngest son, Richard Charles Wyman, passed away on the 29th of August, 1988 in Humbolt county, city of Eureka, CA.

In 2004 I was contacted by a Ms. Marti Wyman Schein - George Wyman's Great granddaughter, who is also a motorbike / motorcycle enthusiast.

My research continues as I find time...

So without further ado, here is the story-

Across America on a Motor Bicycle- 1903

B Y G E O R G E A . W Y M A N :

Part I. Over The Sierras And Through The Snow Sheds

Little more than three miles constituted the first day's travel of my

journey across the American continent. It is just three miles from the

corner of Market and Kearney streets, San Francisco, to the boat that

steams to Vailejo, California, and, leaving the corner formed by those

streets at 2:30 o'clock on the bright afternoon of May 16, less than two

hours later I had passed through the Golden Gate and was in Vallejo

and aboard the "Ark," or houseboat of my friends, Mr. and Mrs.

Brerton, which was anchored there. I slept aboard the "Ark" that night.

At 7:20 o'clock the next morning I said goodbye to my hospitable hosts and to the Pacific, and turned my face toward the ocean that laps the further shore of America. I at once began to go up in the world. I knew I would go higher; also I knew my mount. I was traveling familiar ground. During the previous summer I had made the journey on a California motor bicycle to Reno, Nevada, and knew that crossing the Sierras, even when helped by a motor, was not exactly a path of roses. But it was that tour, nevertheless, that fired me with desire to attempt this longer journey - to become the first motorcyclist to ride from ocean to ocean.

For thirteen miles out of Vallejo the road was a succession of land

waves; one steep hill succeeded by another, but the motor was working like clockwork and covered the distance in but a few moments over the hour, and in the face of a wind the force ot which was constantly increasing. The further I went the harder blew the wind. Finally it actually blew the motor to a standstill~ I promptly dismounted and broke off the muffler. The added power proved equal to the emergency, and the wind ceased to worry. My next dismount was rather sudden. While going well and with no thought of the road I ran full tilt into a patch of sand. I landed ungracefully, but unharmed, ten feet away. The fall, however broke my cyclometer and also cracked the glass of the oil cup in the motor - damage which the plentiful use of tire tape at least temporarily repaired. Entering the splendid farming country of the Sacramento Valley, it is easy to imagine this the garden spot of the world. Magnificent farms, well-kept vineyards and a profusion of peach, pear, and almond orchards line the road; and that scene so common to Californians' eyes and so odd to visitors'- great gangs of pigtailed Chinese at work with the rake and hoe - is everywhere observable.

At Davisville, 59 miles from Vallejo, those always genial and well

meaning prevaricators, the natives, informed me that the road to

Sacramento, which point I had set as the day's destination, was in good shape: and though I knew that in many places the Sacramento River, swollen by the melting snow of the Sierras, had, as is the case each year, overflowed its banks. I trustingly believed them. Alas! for human faith. Eight miles from Davisville the road lost itself in the overflowing river. The water was too deep to navigate on a motor bicycle or any other bicycle, so I faced about and retraced the road for four miles, or until I reached the railroad tracks.

The river and its tributaries, and for several miles the lowlands, are

spanned by trestlework, on which the rails are laid. The crossties of the roadbed proper are not laid with punctilious exactitude, nor are the

intervaling spaces leveled or smoothed. They make uncomfortable and wearying walking: they make bicycle riding of any sort dangerous when it is not absolutely impossible. On the trestles themselves the ties are laid sufficiently close together to make them ride-able - rather

"choppy" riding, it is true, but much faster and less tiresome than

trundling. I walked the road-bed; I "bumped it" across the trestles and

that night, the 17th, I slept in Sacramento, a day's journey of 82 miles and slept soundly.

It was late when I awoke, and almost noon when I left the beautiful

capital of the Golden State. The Sierras and a desolate country were

ahead, and I made preparations accordingly. Sacramento's but 15 feet

above sea level; the summit of the range is 7,015 feet.

Three and a half miles east of Sacramento the high trestle bridge

spanning the main stream of the American River has to be crossed, and from this bridge is obtained a magnificent view of the snow-capped Sierras, "the great barrier that separates the fertile valleys and glorious climate of California from the bleak and barren sagebrush plains, rugged mountains, and forbidding wastes of sand and alkali that, from the summit of the Sierras, stretch away to the eastward for over a thousand miles."

The view from the American River bridge is imposing, encompassing the whole foothill country, which "rolls in broken, irregular billows of forest crowned hill and charming vale, upward and onward to the east; gradually growing more rugged, rocky, and immense, the hills changing to mountains, the vales to canyons until they terminate in bald, hoary peaks whose white, rugged pinnacles seem to penetrate the sky, and stand out in ghostly, shadowy outline against

the azure depths of space beyond."

A few miles from Sacramento is the land of sheep. The country for

miles around is a country of splendid sheep ranches, and the woolly

animals and the sombrero-ed ranchmen are everywhere. Speeding

around a bend in the road I came almost precipitately upon an immense drove which was being driven to Nevada. While the herders swore, the sheep scurried in every direction, fairly piling on top of each other in their eagerness to get out of my path. The timid, bleating creatures even wedged solidly in places. As they were headed in the same direction I was going, it took some time to worry through the drove.

The pastoral aspect of the sheep country gradually gave way to a more rugged landscape, huge boulders dotting the earth and suggesting the approach to the Sierras. At Rocklin the lower foothills are encountered: the stone beneath the surface of the ground makes a firm roadbed and affords stretches of excellent goings. Beyond the foothills the country is rough and steep and stony and redolent of the days of '49. It was here and hereabouts that the gold finds were made and where the rush and "gold fever" were fiercest. Desolation now rules, and only heaps of gravel, water ditches, and abandoned shafts remain to give color to the marvelous narratives of the "oldest inhabitants" that remain. The steep grades also remain, and the little motor was compelled to work for its "mixture". It "chugged" like a panting being up the mountains, and from Auburn to Colfax- 60 miles from Sacramento-where I halted for the night, the help of the pedals was necessary.

When I left Colfax on the morning of May 19, the motor working

grandly, and though the going was up, up, up it carried me along without any effort for nearly 10 miles. Then it overheated, and I had to "nurse" it with oil every three or four miles. It recovered itself during luncheon at Emigrants' Gap, and I prepared for the snow that had been in sight for hours and that the atmosphere told me was not now far ahead. But between the Gap and the snow there was six miles of the vilest road that mortal ever dignified by the term. Then I struck the snow, and as promptly I hurried for the shelter of the snow sheds, without which there would be no travel across continent by the northern route. The snow lies 10, 15, and 20-feet deep on the mountain sides, and ever and anon the deep boom or muffled thud of tremendous slides of "the beautiful" as it pitches into the dark deep canyons or falls with terrific force upon the sheds conveys the grimmest suggestions.

The sheds wind around the mountain sides, their roofs built aslant that

the avalanches of snow and rock hurled from above may glide harmlessly into the chasm below. Stations, section houses, and all else

pertaining to the railways are, of course, built in the dripping and

gloomy, but friendly, shelter of these sheds, where daylight penetrates

only at the short breaks where the railway tracks span a deep gulch or

ravine.

To ride a motor bicycle through the sheds is impossible. I walked, of

course, dragging my machine over the ties for 18 miles by cyclometer

measurement. I was 7 hours in the sheds. It was 15 feet under the snow.

That night I slept at Summit, 7,015 feet above the sea, having ridden -

or walked - 54 miles during the day. The next day, May20, promised

more pleasure, or, rather, I fancied that it did so, l knew that I could go no higher and with dark, damp, dismal snow sheds and the miles of

wearying walking behind me, and a long downgrade before me, my fancy had painted a pleasant picture of, if not smooth, then easy sailing. When I sought my motor bicycle in the morning the picture received its first blur. My can of lubricating oil was missing. The magnificent view that the tip top the mountains afforded lost its charms. I had eyes not even for Donner Lake, the "gem of the Sierras," nestling like a great, lost diamond in its setting of fleecy snow and tall, gaunt pines.

Oil such as I required was not to be had on the snowbound summit nor in the untamed country ahead, and oil I must have - or walk, and walk far. I knew that my supply was in its place just after emerging from the snow sheds the night before, and I reckoned therefore that the now prized can

had dropped off in the snow, and I was determined to hunt for it. I

trudged back a mile and a half. Not an inch of ground or snow escaped search; and when at last a dark object met my gaze I fairly bounded toward it. It was my oil! I think I now know at least a thrill of the joy experienced by the traveler on the desert who discovers an unsuspected pool.

The oil, however was not of immediate aid. It did not help me get

through the dark, damp, dismal tunnel, 1,700 feet long, that afforded the only means of egress from Summit. I walked through that, of course, and emerging, continued to walk, or rather, I tried to walk. Where the road should have been was a wide expanse of snow - deep snow. As there was nothing else to do, I plunged into it and floundered, waded, walked, slipped, and slid to the head of Donner Lake. It took me an hour to cover the short distance. At the Lake the road cleared and to Truckee, 10 miles down the canyon, was in excellent condition for this season of the year. The grade drops 2,400 feet in the 10 miles, and but for the intelligent Truckee citizens I would have bidden good-bye to the Golden State long before I finally did so.

The best and shortest road to Reno? The intelligent citizens, several of

them agreed on the route, and I followed their directions. The result:

Nearly two hours later and after riding 21 miles, I reached Bovo- six

miles by rail from Truckee. After that experience I asked no further

information, but sought the crossties, and although they shook me up

not a little, I made fair time to Verdi- 14 miles. Verdi is the first town in Nevada and about 40 miles from the summit of the Sierras. Looking backward the snow-covered peaks are plainly visible, but one is not many miles across the State line before he realizes that California and Nevada, though they adjoin, are as unlike as regards soil, topography, climate, and all else as two countries between which an ocean rolls.

Nevada is truly the "Sage Brush State." The scrubby plant marks its

approach, and in front, behind, to the right, to the left, on the plains, the hills, everywhere, there is sage brush. It is almost the only evidence of vegetation, and as I left the crossties and traveled the main road, the dull green of the plant had grown monotonous long before I reached Reno, once the throbbing pivot of the gold-seeking hordes attracted by the wealth of the Comstock lodes, located in the mountains in the distance. That most of Reno's glory has departed did not affect my rest that night.

Patented and manufactured by Roy C. Marks, the 'California' motor bicycle was produced from 1901 through 1904; in 1904 this company was sold to "Consolidated Manufacturing" of Toledo, Ohio and became the "Yale" motorcycle. 1904 and 1905 were the only years for the "Yale California" ('Yale' make- 'California' model).

1903, the year of Mr. Wyman's coast-to-coast journey, was a landmark year filled with "first" accomplishments. The first "Harley-Davison" motorcycle was produced, the first year of Henry Ford's famous automobile company; as previously mentioned this was the year of the first automobile crossing of the U.S., the year the first Tour De France bicycle race was run, and the first flight of the Wright Brothers airplan- just to name a few.

George A. Wyman's account was originally published in a series of articles, in his own words, in "The Motorcycle"; a periodical of the time dedicated to motorcycling. "The Motorcycle" was a relatively short-lived periodical, in publication from 1903 until 1906, and yet played a key role in the history of motorcycling. George A. Wyman's incredible account was in their premier issue (Issue 1, Volume1, June 1903).

Unfortunately, this accomplishment was for the most part lost and forgotten. George A. Wyman never received the credit he was due for this historic feat. This series of articles was found and reprinted in a special edition of "Road Rider" magazine (courtesy of the late Roger Hull) in it's complete form in the late 1970's (1979). Yet again it was lost and forgotten until published, in installments, in "The Antique Motorcycle" a publication of the Antique Motorcycle Club of America. Still Mr. Wyman and his accomplishment remained somewhat obscure. In 2002 a friend of mine discovered it and I received in the mail a manila envelope containing a Xerox copy of the Story.

At once I began to read this astonishing account of trial, failure, and triumph. Once finished, I immediately started over again; scarcely believing what I held in my hands! I became enthralled with George Wyman and his incredible feat. I was moved by the great grace and tickled by the humor with which he endured the hardship of this adventure. For years now I have been doing research to find out more about Mr. George A. Wyman, and in July 2003 arrived back home from having finished re-creating his incredible journey to celebrate the 100th anniversary of his achievement.

Born in 1877, in California, George A. Wyman at age 25, who was a member of the Bay City Wheelmen and a bicycle racer, became the first person to cross the Sierra Nevada Mountains with a motor vehicle in 1902; riding his 1 1/2 horsepower California brand motor bicycle to Reno, Nevada for a bicycle-racing event at the Reno Fairgrounds. George arrived on August 31st, 1902 awaiting the arrival of his comrades who brought his racing cycle along by rail one week later for the big race, against rival cyclists the Reno Wheelmen, on Sept. 7, 1902.

(photo of Wyman at a race in Valejo, CA 1902)

It was this trip to Reno that gave Mr. Wyman the inspiration to attempt the first crossing of the American continent on his motor bicycle.

To quote George (from his original 1903 text) while he was traveling over the Sierra mountains:

"I was traveling familiar ground. During the previous summer I had made the journey on a California motor bicycle to Reno, Nevada, and knew that crossing the Sierras, even when helped by a motor, was not exactly a path of roses. But it was that tour, nevertheless, that fired me with the desire to attempt this longer journey - to become the first motorcyclist to ride from ocean to ocean."

George A. Wyman left the corner of Market and Kearney streets in San Francisco, CA at 2:30 P.M on May 16, 1903 and arrived in New York City on July 6, 1903; enduring many hardships and heartbreaks while en route, yet he still manages to tell his story with a great grace, humility, and wit that could only be described as true American spirit.

George did in fact become the first motorcyclist to cross this great land of ours, he then disappeared into obscurity receiving no credit in the pages of our history books for his accomplishment. He also seemed to have just disappeared; we have been doing genealogical research (along with all of the other research concerning the vehicle, the geography of the time, the route traveled, etc.) and have only recently had a breakthrough with the rest of his story. Fortunately, we have been able to discover a little bit about what happened to George A. Wyman after his continental crossing. Here is what we have discovered:

It would appear that George continued to follow his interest in motor vehicles as he worked in different capacities relating to motor vehicles.

According to the 1910 census George had returned to San Francisco where he was working as a mechanic and chauffer, while residing at the Dorel Hotel, 1507 California Street. The 1920 census tells us that George, at age 43, was at this time married with three children, and was working as a second hand automobile dealer / salesman. His wife Nellie Wyman, (maiden name Lovern) age 41, had brought a child into the union; her son Harold, age 19, was a clerk for the Railroad. George and Nellie had also conceived two children of their own- son William (Billy), age 4; and son Richard, age 2. George A. Wyman had relocated from San Francisco by this time. He and his family apparently were now residing in Eureka, California. In the 1930 Census, George is still living in Eureka, CA with his two sons William and Richard. George is now working as an automobile mechanic. There is no record of his wife Nellie residing with him at this point.

Through a search of the Social Security Death Index we discovered that George A. Wyman, the first motorcyclist to cross the Continental United States, left this world November 15, 1959 at age 82 in San Joaquin county, CA. Furthermore, we found that his youngest son, Richard Charles Wyman, passed away on the 29th of August, 1988 in Humbolt county, city of Eureka, CA.

In 2004 I was contacted by a Ms. Marti Wyman Schein - George Wyman's Great granddaughter, who is also a motorbike / motorcycle enthusiast.

My research continues as I find time...

So without further ado, here is the story-

Across America on a Motor Bicycle- 1903

B Y G E O R G E A . W Y M A N :

Part I. Over The Sierras And Through The Snow Sheds

Little more than three miles constituted the first day's travel of my

journey across the American continent. It is just three miles from the

corner of Market and Kearney streets, San Francisco, to the boat that

steams to Vailejo, California, and, leaving the corner formed by those

streets at 2:30 o'clock on the bright afternoon of May 16, less than two

hours later I had passed through the Golden Gate and was in Vallejo

and aboard the "Ark," or houseboat of my friends, Mr. and Mrs.

Brerton, which was anchored there. I slept aboard the "Ark" that night.

At 7:20 o'clock the next morning I said goodbye to my hospitable hosts and to the Pacific, and turned my face toward the ocean that laps the further shore of America. I at once began to go up in the world. I knew I would go higher; also I knew my mount. I was traveling familiar ground. During the previous summer I had made the journey on a California motor bicycle to Reno, Nevada, and knew that crossing the Sierras, even when helped by a motor, was not exactly a path of roses. But it was that tour, nevertheless, that fired me with desire to attempt this longer journey - to become the first motorcyclist to ride from ocean to ocean.

For thirteen miles out of Vallejo the road was a succession of land

waves; one steep hill succeeded by another, but the motor was working like clockwork and covered the distance in but a few moments over the hour, and in the face of a wind the force ot which was constantly increasing. The further I went the harder blew the wind. Finally it actually blew the motor to a standstill~ I promptly dismounted and broke off the muffler. The added power proved equal to the emergency, and the wind ceased to worry. My next dismount was rather sudden. While going well and with no thought of the road I ran full tilt into a patch of sand. I landed ungracefully, but unharmed, ten feet away. The fall, however broke my cyclometer and also cracked the glass of the oil cup in the motor - damage which the plentiful use of tire tape at least temporarily repaired. Entering the splendid farming country of the Sacramento Valley, it is easy to imagine this the garden spot of the world. Magnificent farms, well-kept vineyards and a profusion of peach, pear, and almond orchards line the road; and that scene so common to Californians' eyes and so odd to visitors'- great gangs of pigtailed Chinese at work with the rake and hoe - is everywhere observable.

At Davisville, 59 miles from Vallejo, those always genial and well

meaning prevaricators, the natives, informed me that the road to

Sacramento, which point I had set as the day's destination, was in good shape: and though I knew that in many places the Sacramento River, swollen by the melting snow of the Sierras, had, as is the case each year, overflowed its banks. I trustingly believed them. Alas! for human faith. Eight miles from Davisville the road lost itself in the overflowing river. The water was too deep to navigate on a motor bicycle or any other bicycle, so I faced about and retraced the road for four miles, or until I reached the railroad tracks.

The river and its tributaries, and for several miles the lowlands, are

spanned by trestlework, on which the rails are laid. The crossties of the roadbed proper are not laid with punctilious exactitude, nor are the

intervaling spaces leveled or smoothed. They make uncomfortable and wearying walking: they make bicycle riding of any sort dangerous when it is not absolutely impossible. On the trestles themselves the ties are laid sufficiently close together to make them ride-able - rather

"choppy" riding, it is true, but much faster and less tiresome than

trundling. I walked the road-bed; I "bumped it" across the trestles and

that night, the 17th, I slept in Sacramento, a day's journey of 82 miles and slept soundly.

It was late when I awoke, and almost noon when I left the beautiful

capital of the Golden State. The Sierras and a desolate country were

ahead, and I made preparations accordingly. Sacramento's but 15 feet

above sea level; the summit of the range is 7,015 feet.

Three and a half miles east of Sacramento the high trestle bridge

spanning the main stream of the American River has to be crossed, and from this bridge is obtained a magnificent view of the snow-capped Sierras, "the great barrier that separates the fertile valleys and glorious climate of California from the bleak and barren sagebrush plains, rugged mountains, and forbidding wastes of sand and alkali that, from the summit of the Sierras, stretch away to the eastward for over a thousand miles."

The view from the American River bridge is imposing, encompassing the whole foothill country, which "rolls in broken, irregular billows of forest crowned hill and charming vale, upward and onward to the east; gradually growing more rugged, rocky, and immense, the hills changing to mountains, the vales to canyons until they terminate in bald, hoary peaks whose white, rugged pinnacles seem to penetrate the sky, and stand out in ghostly, shadowy outline against

the azure depths of space beyond."

A few miles from Sacramento is the land of sheep. The country for

miles around is a country of splendid sheep ranches, and the woolly

animals and the sombrero-ed ranchmen are everywhere. Speeding

around a bend in the road I came almost precipitately upon an immense drove which was being driven to Nevada. While the herders swore, the sheep scurried in every direction, fairly piling on top of each other in their eagerness to get out of my path. The timid, bleating creatures even wedged solidly in places. As they were headed in the same direction I was going, it took some time to worry through the drove.

The pastoral aspect of the sheep country gradually gave way to a more rugged landscape, huge boulders dotting the earth and suggesting the approach to the Sierras. At Rocklin the lower foothills are encountered: the stone beneath the surface of the ground makes a firm roadbed and affords stretches of excellent goings. Beyond the foothills the country is rough and steep and stony and redolent of the days of '49. It was here and hereabouts that the gold finds were made and where the rush and "gold fever" were fiercest. Desolation now rules, and only heaps of gravel, water ditches, and abandoned shafts remain to give color to the marvelous narratives of the "oldest inhabitants" that remain. The steep grades also remain, and the little motor was compelled to work for its "mixture". It "chugged" like a panting being up the mountains, and from Auburn to Colfax- 60 miles from Sacramento-where I halted for the night, the help of the pedals was necessary.

When I left Colfax on the morning of May 19, the motor working

grandly, and though the going was up, up, up it carried me along without any effort for nearly 10 miles. Then it overheated, and I had to "nurse" it with oil every three or four miles. It recovered itself during luncheon at Emigrants' Gap, and I prepared for the snow that had been in sight for hours and that the atmosphere told me was not now far ahead. But between the Gap and the snow there was six miles of the vilest road that mortal ever dignified by the term. Then I struck the snow, and as promptly I hurried for the shelter of the snow sheds, without which there would be no travel across continent by the northern route. The snow lies 10, 15, and 20-feet deep on the mountain sides, and ever and anon the deep boom or muffled thud of tremendous slides of "the beautiful" as it pitches into the dark deep canyons or falls with terrific force upon the sheds conveys the grimmest suggestions.

The sheds wind around the mountain sides, their roofs built aslant that

the avalanches of snow and rock hurled from above may glide harmlessly into the chasm below. Stations, section houses, and all else

pertaining to the railways are, of course, built in the dripping and

gloomy, but friendly, shelter of these sheds, where daylight penetrates

only at the short breaks where the railway tracks span a deep gulch or

ravine.

To ride a motor bicycle through the sheds is impossible. I walked, of

course, dragging my machine over the ties for 18 miles by cyclometer

measurement. I was 7 hours in the sheds. It was 15 feet under the snow.

That night I slept at Summit, 7,015 feet above the sea, having ridden -

or walked - 54 miles during the day. The next day, May20, promised

more pleasure, or, rather, I fancied that it did so, l knew that I could go no higher and with dark, damp, dismal snow sheds and the miles of

wearying walking behind me, and a long downgrade before me, my fancy had painted a pleasant picture of, if not smooth, then easy sailing. When I sought my motor bicycle in the morning the picture received its first blur. My can of lubricating oil was missing. The magnificent view that the tip top the mountains afforded lost its charms. I had eyes not even for Donner Lake, the "gem of the Sierras," nestling like a great, lost diamond in its setting of fleecy snow and tall, gaunt pines.

Oil such as I required was not to be had on the snowbound summit nor in the untamed country ahead, and oil I must have - or walk, and walk far. I knew that my supply was in its place just after emerging from the snow sheds the night before, and I reckoned therefore that the now prized can

had dropped off in the snow, and I was determined to hunt for it. I

trudged back a mile and a half. Not an inch of ground or snow escaped search; and when at last a dark object met my gaze I fairly bounded toward it. It was my oil! I think I now know at least a thrill of the joy experienced by the traveler on the desert who discovers an unsuspected pool.

The oil, however was not of immediate aid. It did not help me get

through the dark, damp, dismal tunnel, 1,700 feet long, that afforded the only means of egress from Summit. I walked through that, of course, and emerging, continued to walk, or rather, I tried to walk. Where the road should have been was a wide expanse of snow - deep snow. As there was nothing else to do, I plunged into it and floundered, waded, walked, slipped, and slid to the head of Donner Lake. It took me an hour to cover the short distance. At the Lake the road cleared and to Truckee, 10 miles down the canyon, was in excellent condition for this season of the year. The grade drops 2,400 feet in the 10 miles, and but for the intelligent Truckee citizens I would have bidden good-bye to the Golden State long before I finally did so.

The best and shortest road to Reno? The intelligent citizens, several of

them agreed on the route, and I followed their directions. The result:

Nearly two hours later and after riding 21 miles, I reached Bovo- six

miles by rail from Truckee. After that experience I asked no further

information, but sought the crossties, and although they shook me up

not a little, I made fair time to Verdi- 14 miles. Verdi is the first town in Nevada and about 40 miles from the summit of the Sierras. Looking backward the snow-covered peaks are plainly visible, but one is not many miles across the State line before he realizes that California and Nevada, though they adjoin, are as unlike as regards soil, topography, climate, and all else as two countries between which an ocean rolls.

Nevada is truly the "Sage Brush State." The scrubby plant marks its

approach, and in front, behind, to the right, to the left, on the plains, the hills, everywhere, there is sage brush. It is almost the only evidence of vegetation, and as I left the crossties and traveled the main road, the dull green of the plant had grown monotonous long before I reached Reno, once the throbbing pivot of the gold-seeking hordes attracted by the wealth of the Comstock lodes, located in the mountains in the distance. That most of Reno's glory has departed did not affect my rest that night.

Last edited by a moderator: